BCI: Why the ‘Better Cotton Initiative’ is not always better

Buying cotton products labelled as ‘preferred and more sustainable’ is not necessarily as ethical as it sounds to many consumers, and even to some brands. Considerable amounts of cotton promoted by the BCI (Better Cotton Initiative) have been harvested using forced labour.This article will brief you on the systematic oppression of the Muslim Uighur minority of the Xinjiang province. Additionally, how it relates to the compromised production of clothes purchased by Western brands. Lastly, how the structure of the BCI had allowed atrocities to take place under the label of “sustainable cotton”.

Detainees of structural oppression

Since 2016, the Uighurs have been detained and forced to work under inhumane conditions. With the end-product being marketed as ‘sustainable’ cotton. By now, up to two million people have been forced into detention and ‘re-education’ camps. In prison-like facilities, the Uighurs are chained to walls for weeks, denied access to sanitation facilities and medicine, and tortured with electric shocks and lashes.

The detainees who survive are transferred for ‘re-education’. Having completed the two year “re-education program”, they are taken to factories where they are forced to produce goods, under the name of several internationally known western brands. Still under constant surveillance. According to the Fair Labor Association, some people might get paid, while others might not. At the same time, it says that some may be able to come and go while others may not. In any of these cases, since the people are not working under their own free will, it is forced labour.

Cotton harvested by school children

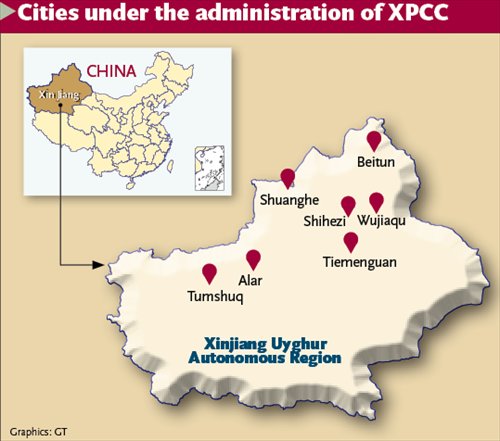

Child labour in connection with the Chinese cotton harvest has been reported since at least 2006. In 2008, one million school children were forced to pick cotton, as part of so-called “work-study” and “help with agriculture” programs. In response to accusations of child-exploitation, the XPCC (the main cotton producer in Xinjiang) and XUAR (Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region) told Radio Free Asia in 2017 that “women and children pick cotton and perform other duties for their own family’s benefit,” rather than as part of a “re-education through labor” program. However, this has been contradicted by various NGOs such as Human Rights Watch , Fair Labour Association and Amnesty International.

BCI: “An increasingly untenable operating environment”

The multi stakeholder initiative, BCI, sourced its cotton from cotton fields in, amongst others, the Xinjiang province up until October 21st 2020. While the organisation less than a year ago failed to acknowledge that forced labour on BCI farms was an issue, it has now recognised that “sustained allegations of forced labour and other human rights abuses in XUAR have contributed to an increasingly untenable operating environment”.

BCI presence in China: A positive impact on farmers?

In the beginning of this year, BCI was confronted with a series of questions about increased forced labour concerns in the Xinjiang region. In response hereto, BCI did not only deny its involvement of forced labor on farms within BCI Programmes. It actually claimed that BCI’s presence in China has had a “positive impact on farmers [and] their families” as well as on the environment. The organisation also claimed that investigations conducted by direct or indirect third-party sources did not find any evidence of forced labor on the farms from which BCI sources its cotton. BCI added that it “is a robust, well-established and well-managed multi-stakeholder organisation with strong governance bodies and related procedures”.

Elsewhere, BCI has taken a different approach. Brands have withdrawn production from Uzbekistan due to concerns about forced labour in its cotton industry. It has been suggested that this was what led BCI to boycott Uzbekistan, citing clear and undeniable evidence that the government has ‘voluntarily mobilised parts of its workforce […] to pick cotton’. However, expert commentators report that the situation in Xinjiang is far worse than in Uzbekistan.

How scale trumps stringency

While BCI has ceased all field level activities, it ignored or downplayed the importance of forced labour for a significant amount of time. How did it come to this?

Attempting to answer this question, one must understand that the objective of BCI has been to improve the sustainability of conventional cotton rather than targeting a niche market, such as organic cotton. A group of scholars from, amongst others, Roskilde University, Denmark, have examined how BCI operates. They have found that BCI has chosen a high level of process control and efficiency over stakeholder inclusion. A small group of stakeholders quickly reaches a consensus upon which it can act. As a result, efficiency came at the cost of representation of human rights and working conditions.

BCI has also prioritized scaling up the initiative, at the expense of stringent standards. The higher the standard, the harder it is to scale up an initiative since fewer stakeholders will be able to join. This, together with the emphasis on keeping Better Cotton (cotton made by BCI trained farmers) prices appealingly affordable for brands, has brought BCI considerable success. Its market share is currently at 22% of all cotton produced in the world. This is an enormous impact. To put this in perspective, all organic cotton accounts for less than 1% of the global cotton production.

Zooming out: China – the driving force for the atrocities

The detention of Uighurs in re-education camps was initially fiercely denied by the Chinese authorities. Later it was proudly presented as a success project of “humane management and care”, similar to summer camps, combating religious extremism and crime. As mentioned earlier, this has been contradicted. Individual facilities have been registered by ASPI and their locations made publicly available through an interactive map.

Uighur exploitation is a part of the Chinese supply chain in several other industries, such as the electronics and automobile industry, both in and outside of the Xinjiang province. According to Maplecroft, a global risk analysis firm, “all manufacturing supply chains linked to China are at risk of being associated with forced labour and other abuses in the region“. Also, due diligence on the part of brands is unlikely to prevent these abuses, since the Chinese government will do its best to make them (the abuses) untraceable. This view is supported by the Fair Labour Association.

The immediate responsibility for the cultural genocide and oppression of Uighurs in China lies with the Chinese government. However, one cannot disregard the implication of individual facilities, organisations, or textile brands profiting from such horrendous exploitation, implicitly condoning/endorsing human rights violations, and financially supporting the government which commits them.

How do we approach the BCI issue?

Tekstilrevolutionens usual approach is to challenge those responsible for poor working conditions to improve them. When brands suddenly withdraw demand for a service, the workers are left without a job. Thus harming the vulnerable rather than disciplining the responsible parties.

However, this is an unusual case. It is difficult to imagine how textile companies alone, regardless of their size, could convince the Chinese government to reverse their policy towards Uighurs by appealing to conscience alone. Since the Uighur workers are not benefiting financially from their labour, there seems little benefit in continuing to reward the system of oppression by providing it with further business. However, the BCI has, according to their latest report, worked with 81,043 farmers in China alone in 2018-2019. Also, their comparison with non-BCI farmers from 2017-2018 shows positive impacts on profit, pesticides water usage and more.

Now that BCI has announced closing its production in Xinjiang – not in other areas of China – we were interested in hearing from the textile companies that buy BCI cotton, and thereby have been complicit. We contacted 15 of the larger brands, of which a few got back to us. All brands acknowledged that this was indeed a major concern and several answered our questions in detail. All of the brands continue to see BCI as a trusted partner. It was recommended that we contact BCI directly and read BCI’s statement on the issue.

How this issue should be approached is not easy. However, we have made some recommendations for you. Both as a consumer, a brand or an employee in the political field. These may guide you in a better direction, and help reflect on the most important issues.

Recommendations

Political arena

- Forge alliances to put political pressure on China to cease operation of forced labour camps and cultural genocide.

- Invest in credible supply chain mapping innovations. Creating a better overview of the whole supply chain strengthens transparency as you can track transactions from harvesting the fibre to the finished product. This enables consumers to hold non-compliance accountable, and invest in best practice.

- Enforce a law that makes transparency mandatory throughout all the links of the supply chain.

Industry

- Form alliances to avoid products made in China. Recent reports describe government-mandated employment schemes for Uyghurs using forced labor outside of Xinjiang. Thus, even when choosing a supplier in a region outside of Xinjiang, you cannot be certain of good labour practices.

- Ensure that a certification has been verified through a third party auditing scheme.

- Pay attention to the way the grievance structure is set up. Ensure that interviews with garment workers are conducted in a way that allows the respective interviewee to express concerns without any negative consequences.

Consumers

- Do not confuse initiatives focused on raising the bar for mainstream production with certifications that have very stringent criteria. It is vital to understand that both have strengths and weaknesses. It is important to keep an open mind, and stay informed about which initiative is doing what.

- Support independent media. By subscribing to independent journals, you run less of a risk of supporting journalism that is compromised by brand funding. You also support the work of journalists investigating situations like those in Xinjiang, which provide objective data. This may help by exposing atrocities like those befalling the Uighurs, and preventing others from happening.

- Ask questions before you buy. Even if the person in front of you cannot answer, enough questions will lead to them being raised further up in the organisation.

About BCIThe Better Cotton Initiative (BCI) is a global not-for-profit organisation and a cotton sustainability programme. It aims to make cotton production more sustainable by intending to minimize the negative impact of fertilisers and pesticides, and care for water, soil health and natural habitats. Goal

How |

02.11.2020

Authors: Markus & Marie Editor: Elizabeth